Barracuda on Black Bass Tackle

This article was originally by Van Campen Heilner and published in 1920.

Modern preface by Fiscian.com: Some specific talk about rods and lines, is not applicable today unless you are fishing with circa 1920s equipment. However, the logic is still sound by modern standards, you can target barracuda with lighter tackle one might use for bass fishing today. If you are not familiar with the phrase black bass fishing, check out our Q&A here.

(Zane Grey said of this story: “The few of us who have hooked barracuda on light tackle know him as a marvelous performer. Van Campen Heilner wrote about a barracuda he caught on a bass rod, and he is not likely to forget it, nor will the reader of the story forget it.”)

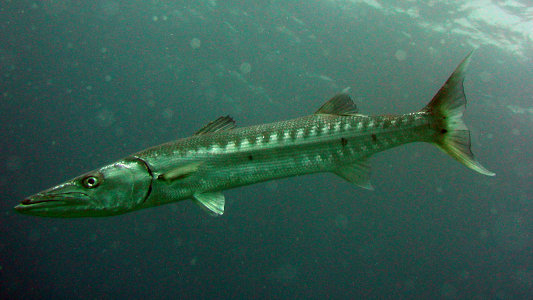

The Florida angler, as a rule, knows the barracuda—or barracouta as it is often called there— viewed from one end of a six-foot reef rod, automatic drag and eighteen-thread line, as a game fish, and a fighter. But if he knew the marvelous gameness displayed by the barracuda when angled for on the tackle one ordinarily uses in fresh water, he would never again seek this fish—one of the sportiest propositions of Southern seas—with a reef rod.

My earlier fishing for barracuda in Florida had been done with my reef outfit. And at that time I respected the fish as well worth the efforts of the most expert angler. Had I known then what I know now: that these wolves of the sea become veritable demons of strength endurance when fought on a light rod, would have thrown my heavy outfit into the sea. After four years' experience with barracuda on extremely light tackle, I consider them the match for gameness, spectacular leaping and fighting ability, of any tarpon that ever swam. And I have taken tarpon on the identically same equipment.

One winter the idea occurred to me to try for these pike-like fishes with the rod I had always employed when angling for bass in fresh water. I showed this outfit, a four and one-half ounce, five foot Heddon bait casting rod and a 3/0 surf reel holding eleven hundred feet of nine-thread line to Captain Anderson. He laughed at me. He took the line in his hands and snapped it with the merest jerk. “Why!” he assured me, “that wouldn't so much as hold a needlefish, let alone a barracuda!” But I would not be discouraged. “We will try it, anyway,” I told him. He shrugged his shoulders. “All right,” he said, “we will try.”

It was during the early part of March. We were anchored among the Ragged Keys, a small chain of islands, some fifteen miles in a southeasterly direction from Miami. Between these keys ran swift deep channels, varying in width from a hundred yards to a quarter of a mile. Elsewhere the water was very shallow, with a sandy or marl bottom. In the channels the banks shelved off into fifteen and twenty feet of water. Great coral heads dotted the ocean floor, and under these we would often take fat luscious crawfish, which in my opinion, when prepared in the right manner, are more delicious than lobster.

On the incoming tide, these cuts and channels would be thronged with fishes, barracuda especially. Rowing along in a skiff, one could see these huge wolfish fellows floating along the edge of the bank, or dashing through a school of terrified mullet. The marine life was varied and ever changing. I once witnessed, among these same keys, a death battle between a whipray and a shark. The ray continually leaped high into the air, falling with a report 'that could be heard for miles. The shark finally got a mortal grip on the ray and shook it like a terrier would a rat. It bit great pieces out of that ray. The water all around the scene of the conflict was crimsoned with blood. It was a disgusting but thrilling sight.

We set out in our small launch, Cap steering from the bow and I trolling from the stern. Large quantities of mullet had come in on the rising tide and hundreds of pelicans were feeding on them. The pelicans would sail gracefully along some distance above the water until they sighted fish. Then they would turn and, folding their wings, plunge downward, striking the water with an awkward splash. I have frequently been deceived at a distance by feeding pelicans. The splash they make as they hit the water, when seen out of the corner of one's eye, greatly resembles that made by a leaping fish.

We had only proceeded a short distance when I had a violent strike. The line whipped off the reel, the rod nearly described a circle and I blistered my thumbs badly endeavoring to check the swift rush.

Soon I was rewarded by the sight of a barracuda, as he cleared the blue green waters of the channel, some four hundred feet away. I was astonished at the fight the fish gave me. Back and forth it rushed, often shooting into the air amidst a great smother of foam. At one time I could see the great black splotches on his belly as it came out broadside on its tail.

I was fearful of placing too much strain on the rod, for I did not know then what it could stand, I played him very gingerly and in forty minutes had him alongside of the boat. After weighing him—twenty-six pounds and a fraction—we released him. The hook had caught in a corner of his jaw and he was uninjured.

I was much elated over this performance. It demonstrated to my satisfaction that my light tackle was adequate for these fish. That one barracuda had given me the confidence I needed, and an unquenchable thirst for more. And I was determined I should have more.

We were forced the next day to return to Miami, as Captain Anderson's time with me was up. But I hastened with the news to Charlie Miller, an old boatman of mine, who had just arrived from the North.

“I think, Mister Van,” he confided to me, “this recent cold spell we have had down here has affected your brain.” “Has it?” I rejoined. “Fill up the Wahoo with gas and provision and let's go down to the keys and see.” The Wahoo was a fast launch. She made between seventeen and eighteen miles per hour. And Charlie had an arrangement whereby he could use kerosene as well as gasoline, which increased the speed another mile. So we lost no time in reaching Ragged Keys.

It seemed good to be back once more among those emerald islands and traversing those enchanted channels with their myriad fish life. I celebrated by taking a long invigorating swim on one of the shallow banks, out of reach of any marauding sharks. While I was loafing around in the water, I came across some coral rock lying partly submerged. In a pool in this rock, I discovered what appeared to be a live crawfish, but without any head. I preserved this queer object, and later learned from the American Museum of Natural History that it was an uncommon specimen of Crustacea. Whether it was good eating or not, I have forgotten. That afternoon on the incoming tide we started trolling. The first cut produced nothing outside of two small groupers, which we later utilized in a savory chowder.

The second cut proved a new trial for my rod. As we were passing out of the far end, some unknown thing seized my mullet with a vicious jerk. Out sped the line and we watched for the leap thatwould tell of a barracuda. But no leap occurred. I suggested to Charlie that he start up after the fish as it showed no inclination to stop. We followed it back through the pass and into the shallower waters of the bay. Here the strain seemed to tell and after it made one or two long ineffectual rushes to regain the channel, it came to boat. It was a seventeen-pound muttonfish, a reddish looking thing somewhat on the order of a snapper. But it was a splendid antagonist. I had it mounted and it has always proved a pleasant reminder of Latitude N. 25°.

“Let's see you try it, Charlie,” I said, and handed him the rod. He took it warily, for although Charlie is a fine rodsman, I think, perhaps, this was the lightest he had ever handled in this kind of fishing. I ran the launch back through the channel and hooked him on to a fourteen-pound barracuda. He played it quickly and easily and soon brought it, belly up, to boat. “I am converted, Mister Van,” he said, with a look of wonder. “I have whipped this fish to a standstill, in the most sportsmanlike way, and he deserves his liberty.”

Off the end of the northernmost key, there was a large rock which protruded from the water at certain stages of the tide. It was devoid of vegetation with the exception of one straggly piece of mangrove which struggled pluckily against the buffets of contending winds and seas. In all the times I have visited Ragged Keys, I have never—and here is a remarkable thing—I have never circled this rock with fresh bait without receiving a strike from something.

That night, as we were returning to the Wahoo, we passed the rock and saw several barracuda—big ones they looked, too—breaking among some mullet. We were out of bait, so did not stop, but we made up our minds we should thoroughly investigate those waters in the morning. We went out after supper and netted some bait and the next morning early were out at the rock. The tide was nearly high and was moving in very slowly, almost at a standstill, in fact. I expressed some doubts to Charlie as to whether the fish would strike. For it seemed that on the change of the tide, as if by magic, they would all disappear. He said he thought he had seen a barracuda over near the edge of the bank, so we commenced circling. We had not gone far—in reality, not half way 'round the rock—when I received a tremendous strike. It was so unexpected that the rod was nearly jerked from my hands. Before I could recover from my surprise over six hundred feet of line had been stripped from the reel, I had never had a barracuda take this much line on its first rush before. I was stunned. So great was the friction on the reel that I was forced to hold it under water to prevent it from overheating. “For goodness' sake!” I shouted. “Shut off the engine and row—row for your life!”

Then he came out of the water. In a great smother of foam he lashed his head from side to side, and then sounded. Charlie had thrown me another thumbstall and I slipped this on my left thumb. The boat was now gaining some headway under Charlie's masterful strokes, and I began to breathe easier. He headed away from the rock and for the nearest channel, through which deep water led to the sea. Despite our frantic efforts, he seemed to be outdistancing us and my heart sank like a stone. “Oh, Lord!” I groaned. “What the devil is the matter with you? Row!— Row, can't you!” Charlie swore at me. He called me several very bad names, I believe I reciprocated in kind. We were both mad; mad at each other and at the fish. The line now was almost out. I could see the copper spool to which it was tied. And to make matters worse, the barracuda crossed the bank which separated us from the next channel and gained the deep water. The water on this bank was too shallow to float the launch and things looked desperate. He started jumping. But all we could see was the splash. I dared not place any strain whatsoever on him. So much line was out that I feared it would break of its own weight. At any second I expected to hear it snap like a taut fiddle string. But suddenly the luck turned. I gained a few feet. Then I gained some more. Then he jumped and I lost it all. But it was a tired looking jump, and I quickly regained what he had taken out.

Slowly—very slowly—I took in line. Now, after an agonizing moment, I had him out of the channel and onto the bar! Here he made some more savage rushes, leaping into the air and shaking his head violently. But I held him. It was ticklish work to get him in. When I pumped, I was forced to lay the rod along my left arm and lift cautiously and gradually. Then I would drop the tip sharply and reel swiftly. My pulse throbbed like a trip-hammer. The sweat rotled off my face and hands till my clothing was saturated. I cursed. I prayed. I worked. And I gained! Now he was across the bar, now only a few yards from us. He swam slowly in a circle, the line cutting through the water with a peculiar zipping sound. Charlie backed and filled on the oars and kept the fish constantly in front of me. And then we made him out. He looked a monster. In he came, deep down, and shaking his head from time to time. When he saw the boat, he turned and ran, but I stopped him short of two hundred feet. This time he came easier.

Charlie shipped the oars and reached for the gaff. I now held the fish with my thumb only. He was sorely fatigued. He made a turn. I strained hard and brought him to the surface. “Careful! C-a-r-e-f-u-l!” I panted. “Stay. where you are. I'll lead him to you!” There was a quick movement on Charlie's part, a great splashing that deluged us both, and the great barracuda was in the bottom of the boat. He thwacked the boards with his tail twice— then lay still—dead. When we got back to the Wahoo we lifted him onto the scales. He weighed 44 pounds 3 ounces; length, 56 inches; girth, 18 inches; time, 1 hour 12 minutes.

As he floats motionless upon his panel above my desk at home, his white fangs bared in defiance, his lithe tigerish body suggestive of all his great strength and endurance, I cannot help but feel whenever I gaze up at him, like bowing in acknowledgment to one who, in pluck and gameness, outfought any barracuda for which I have ever angled. In the three succeeding days I took, on the same tackle, fourteen barracuda, the largest of which weighed thirty-seven pounds, I have also, since then, taken a fifty-six pound tarpon on the same outfit. I sincerely hope that some of my readers will try for large fish on correspondingly light tackle. For I am sure that they will find, as did I, that the fish then shows off to its best advantage, and though the odds be twenty to one in its favor, the sport afforded is nothing sort of wonderful.