The Record Bonefish

This article was originally by B. F. Peck and published in 1920.

Modern preface by Fiscian.com: While this fish is no longer the biggest Bonefish ever, it is still a trophy fish by modern standards. No additional information is needed for the modern reader to enjoy this article. Messrs. is just the plural version of Mr. The second half of the article talks about Bonefish if you are not already familiar with them.

The time was Sunday, March 9th; the place Bimini Islands, about forty-five miles due east from Miami. We were off the good ship Buffalo, Captain William Layton commanding. Our party consisted of Messrs. George and Louis Hilsendegen, of Detroit; Charles D. Velie, of Minneapolis, and myself. Our guide had come aboard early in the morning to remind us that it was Sunday, “a day set apart,” and to say that as he was a deacon in the church, it would be impossible for him to accompany us. He was quite willing, however, to provide a substitute, less scrupulous than he, and we went to a point about three miles from the dock, where we made what the natives call a “guessdrop,” and waited for the bonefish to come in.

Charley and Lou, with the guide, were in one boat; George and I, with Roy Tingley, one of our crew, were in the other. We had waited two hours without a strike. No one had even thought he had a strike. I had begun to think there was “no such animal.” Then one came, we saw him! He took my conch! Nibble, nibble, nibble—wait, wait, wait.

Then I struck. He was away like a flash of lightning. Zip, zip, zip, went the line for at least two hundred feet, then he paused, for a second only, and was off again for at least three hundred feet more. I was wondering if he would ever stop, when George, likewise anxious, asked how much line I had. We both looked at the spool. It was something less than the thickness of a thumb—not one hundred of the six hundred feet were left on it. Then he swerved, churning the water with foam, and came toward the boat. Then a rush to the right of from seventy-five to one hundred feet, then a stop. Then toward the boat again to about one hundred feet from the stern. Then another rush to the right and a stop. Then he started to circle the boat. Once around, twice around. “He will go seven times,” said George. Well, he went six and a half times, then darted under the boat. My heart sank, but I dropped the tip of my rod into the water, and prayed. This little recognition of the Sabbath, “a day set apart,” had its effect. He came back, circled the boat once more, making seven and a half times in all, and turned on his side, all in. I brought him to the boat. Our net was too small, and we dared not risk our prize by trying to lift him in with our hands, so Roy resorted to the gaff.

We weighed him immediately. The scales showed between 13&7/8 and 14 pounds. I signaled “14” to Charley and Lou in the other boat. Charley, who held the previous record at 9&1/2 pounds, replied with the Aztec sign. The scales were tested when we came ashore, and found to be a trifle heavy, so that, assuming the original weight to be 13&7/8 pounds, instead of 14, and making proper allowance for the scales, the weight of the fish, when taken from the water, was 13&3/4 pounds, strong.

The natives, or some of them, thought “perhaps and maybe” they had once seen a larger fish caught in a net, but in a conversation among themselves, which we were not supposed to hear, they admitted this was the largest bonefish ever caught at Bimini. The books give ten pounds as the utmost limit of weight. Fishermen will appreciate my sensations when the scales told the story of this unprecedented capture. I certainly felt "...like some watcher of the skies, When a new planet swims within his ken.” We photographed our prize; the village carpenter made a coffin and the natives brought flowers. We appointed one of them a special custodian for ten days, when we returned to Miami. By this time we were reasonably sure he was dead and felt safe in committing the remains to Brigham, the Miami taxidermist, whose assistant, W. W. Worth, of Wildwood, NJ mounted them. He or they are now hanging in my office at Moline, Illinois. All “doubting Thomases” are cordially invited to call.

The time employed in the capture was twenty-seven minutes. The tackle consisted of a six-ounce rod, nine-thread line, free spool. The fish measured thirtyone inches from tip to tip, measuring straight on the side, and seventeen inches in girth. For the benefit of the many novices and the by no means few experienced anglers who have not made the acquaintance of the bonefish, a brief description of this rare fish may be in order.

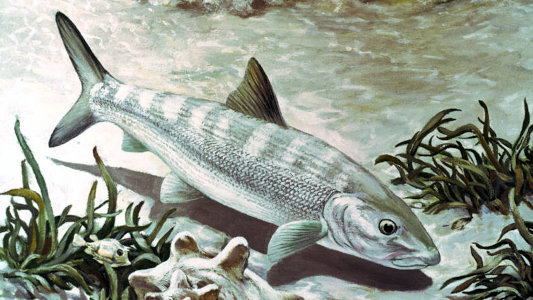

His family name (and he is the only member of the family) is Albula vulpes, meaning “little white fox”. He is found only in the waters of Biscayne Bay and the West Indies. It is believed by some fishermen that the latter waters the real home of this fish, and that those found in Biscayne Bay are the intrepid spirits who have ventured to cross the Gulf Stream. In Cuba, he is called what is pronounced “leetha,” meaning “the swift.” Many fishermen, some of them writers and authorities, have confused him with the so-called bonefish (Elops saurus), also called the lady fish, which is found on both the western and eastern coasts of Florida, and as far north as New York. The two fish are entirely distinct, both in habits and physical characteristics. No record exists of the capture of a true bonefish north of the Indian River. The so-called bonefish, or lady fish, has been caught off the coast of Long Island. The true bonefish never leaps from the water. The lady fish, in the language of the late Senator Quay, are “as frantic in their leaps as the tarpon.” The difference in physical characteristics is apparent at a glance. Harris, in his work on American fishes, says:

"The true bonefish is much stouter in build, has large scales and is brilliantly silver in color, shadirg into olive. The so-called bonefish has much smaller scales, has also a bright silver color, but in lieu of an olivaceous shading, there is a distinct but soft bluish coloration, extending from the shoulder to the fleshy part of the tail.”

The bonefish is a bottom feeder. He eats all crustacea—hermit crabs, conch and clam are the common baits. He comes into the shallow banks for the food which the incoming tide provides in greater abundance. He, or they, for they often come in numbers, may be plainly seen, sometimes swimming along, fin and tail out of water, sometimes standing on their heads feeding on the bottom, tail only showing, sometimes resembling a dark shadow in the water moving with the utmost swiftness. Again, his presence is revealed only by a wake. He is timid in the extreme. A bump or unusual noise in the boat, or the shadow of a bird flying overhead, would cause him to disappear. Most fishermen prefer to pole along the banks quietly until some sign denotes the presence of the fish, then drop, and cast in the vicinity. This stalking the game, as it were, is a novelty in fishing which will appeal to all sportsmen.

If fortune does not favor you, and no sign is given, the fisherman can only stop at a likely spot and make what the Biminians call a “guess-drop,” and wait. You may see him coming; you may not. Often, the first intimation is a gentle pull on your line. This means he is sucking the bait. You wait. A more decided pull will come, when he gets the bait to the rear of his mouth and sets his crushers upon it—then you strike—and the party's on. The fastest, gamest fish that swims is on your hook, and may the best man win.

There is no record of the taking of a true bonefish with rod and reel, prior to 1893. The honor of the first capture belongs to J. B. McFerrand, Esq., of Louisville, Ky. In a letter written by him, dated January 11, 1902, and published in Gregg's work on Florida Fishes, he tells the story of the capture saying in part:

“For three solid weeks, I worked and worried over these fishes. I could hear of no one who had ever caught one with rod and reel, and the natives said it could not be done. No sooner would I get within casting distance and the lead would strike the water, when away they would go like a badly scared flock of quail. At last, about worried out, I had determined to give it up as a bad job, when I discovered a space of about an acre of bare sand bottom adjoining a small channel, which connected with a small inlet and beyond that spot was a shallow bay, the bottom of which was covered by a heavy growth of grass. We lay on the far side of that bare spot about ten minutes with the line out toward the edge of that little channel, when I saw eight or ten of the hopefuls poke their noses from the edge of the channel, and within five minutes I had my fish hooked. Well, I had been angling in many waters, far and near, salt and fresh, and caught, as I thought, about all the fishes known in this country, but here was a sensation, indeed—a new edition of chained lightning, and that greased. . . . Only an old hunter, who has trailed his buck through the forest, until footsore and heartsick, finally bringing him down with a well-directed shot, can appreciate my feelings. ...They fight to a finish every time. I have had a seven-pound fish run five hundred feet straight away without a pause. I am sure that unhampered nothing with fins or scales can catch them, unless it is the porpoise. If the bonefish were as large as the tarpon, with speed increased with size, no rod and reel could make him captive. Pound for pound, the bonefish is far and away the king of all swimmers, and the only objection I can urge against him is that an experience with him forever disqualifies one for all other fishing. But we are always looking for the new sensation, and Bonefish is it.”